Kinkly contributor and expert reviewer Dr. Laura McGuire has authored a book entitled "Creating Cultures of Consent: A Guide for Parents and Educators." We are pleased to present an excerpt here, which focuses on an issue so important to all of us at Kinkly!

We are living in a time when the word consent is a word on the tip of so many tongues. Many have embraced it wholeheartedly, while some have reservations and others find offense in its basic tenants. The reason for these variations in reactions is the fact that this entire conversation is so new to the Western world. We didn’t grow up with these concepts and hearing that the way we may have joked, been complacent, and overlooked things laid a foundation for the major crises’ we are observing today can feel far-fetched and extreme. We can’t be that bad, right?

As a parents, we know how much already weighs on us. As teachers, we are also well aware that the standards and statutes, we are asked to follow can flood our days and already keeps us up at night. To say there is another box to check, another thing to fear, and a new way you are screwing up is not the message we want you to get from this book. In fact, it’s quite the opposite.

Our hope is that by guiding you—whether you are a parent, and educator, or concerned and caring member of the community —on this journey you walk away feeling empowered and excited. We cannot hide our heads in the sand or say that this isn’t something we have to address because we do explicitly.

Every single day children, teens, adults, and the elderly are sexually harassed, abused, and assaulted.. You probably know at least one survivor of this kind of abuse, or you may identify as one yourself. You know this happens and perhaps on a scale far greater than anyone will ever truly quantify. As people who interact with kids and teens, we want to protect them but often feel overwhelmed by the question of how. That is why this book was written, to provide some answers and tools to what works and how to lay a foundation for shifting from a culture that fosters abuse to one that eradicates it.

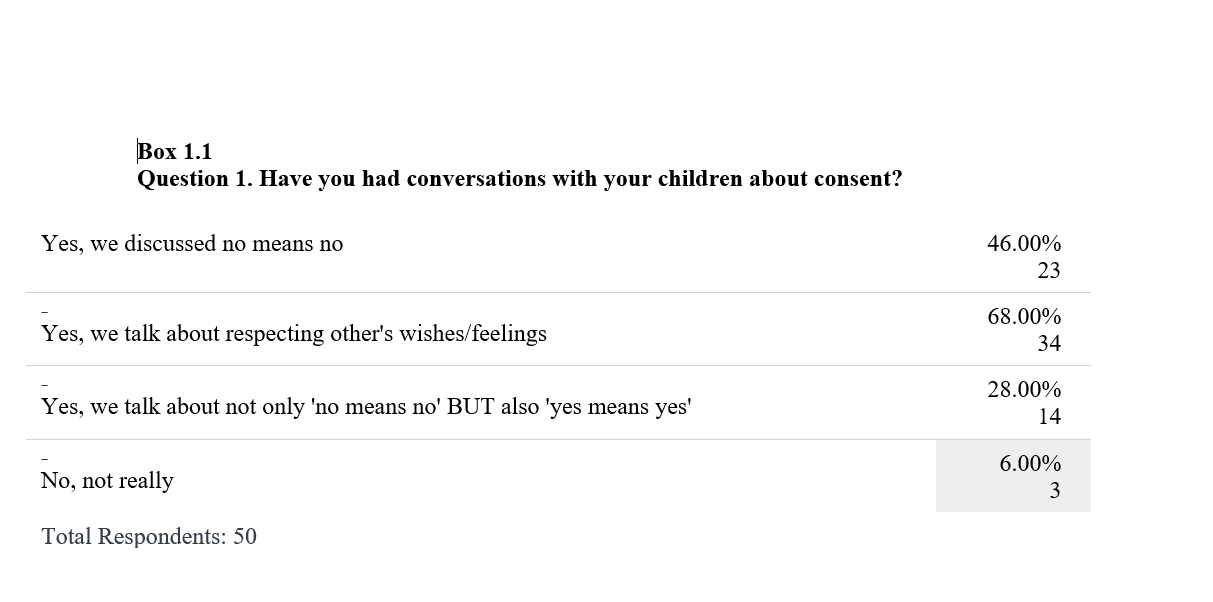

In the spring of 2019, I designed and disseminated a survey on what parents teach their children about consent. It was sent it out through Survey Monkey and promoted it on social media and through email marketing. The results from the 50 parents who participated were incredibly insightful as to the current conversations progressive parents are having with their children.

The survey questions and responses were as follows:

The results of this small sampling of parents reflect much of what we see out in the field: parents and educators want to talk about consent, and most do in one way or another. We can see in question 1 that most parents feel that they have addressed consent by talking about respecting people’s feelings. We often hear men say that they understand consent because they were taught to “respect women.” While this is a start, and very well intended, it does not adequately address the complexities of interpersonal and gender-based violence. Nor does it do anything to address the violence that boys, men, non-binary, and transgender people face. The same is true for the response that parents are still sticking to the slogan ‘no means no.’

The problem then is not that consent is being ignored as a conversation that parents are having with their children (very few said they do not discuss it), it is that such a deep and broad topic is often boiled down in ways that do not cover the most relevant aspects of this discussion. Should respecting each other and stopping at ‘no’ be a launching point for discussing consent with children? Yes. Should it be the beginning, middle, and end? No.

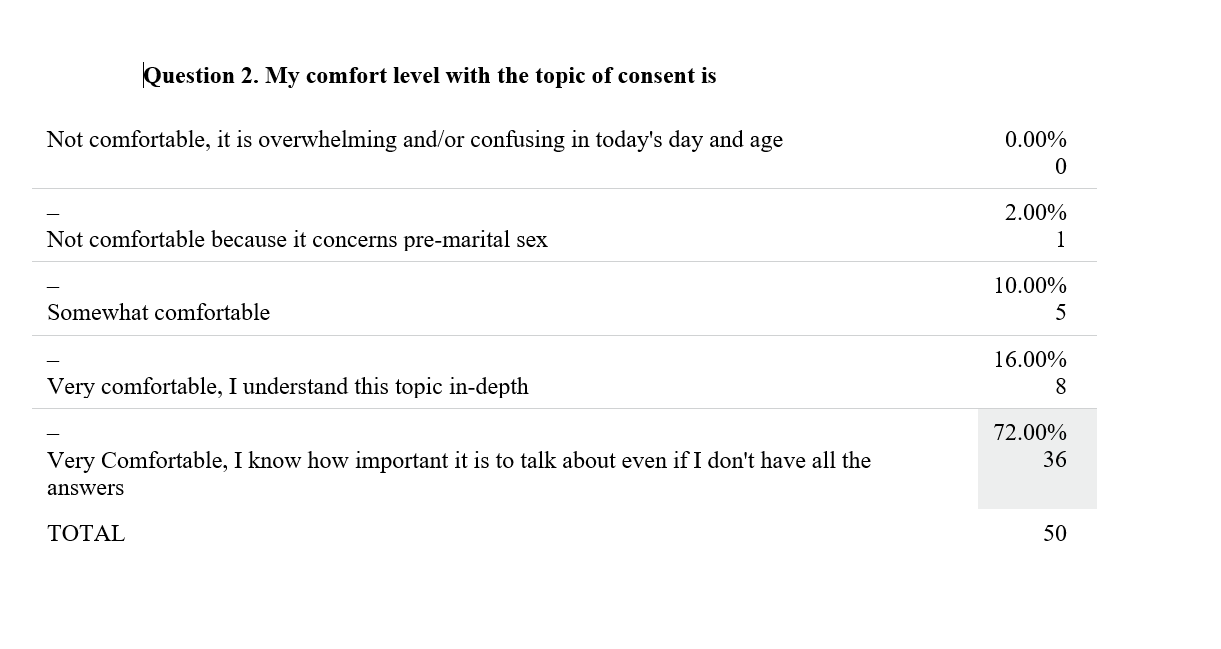

It is encouraging to see that in question two most parents replied far and above on average that they do feel comfortable talking to their children about consent, even though they may be confused or overwhelmed by aspects of it. This is terrific news because it means that there is an opportunity to continue educating parents and teachers on how to feel better equipped in exploring consent conversations with youth. The greatest obstacle is reaching those who feel uncomfortable with the topic entirely.

Only one parent responded that they feel consent is a conversation about pre-marital sex and none of the respondents said no straight out. The media exposure to the topic is creating a positive ripple effect: parents see that this something that must be discussed and that they need to start earlier than they previously thought. Even when they know that there are aspects of where consent conversations are going that they don’t understand, they still know that having an open dialogue with their children and planting whatever seeds they can offer is better than burying their head in the sand.

The topics that parents are most comfortable talking to their children about regarding consent were “no means no,” “bodily autonomy,” and “verbal and non-verbal consent.” This is consistent with the messages we have received culturally on sexual assault prevention over the past 30 years and mirrors some of the recent conversations we have seen in the media on respecting children’s personal boundaries.

The least discussed of options presented were token resistance/compliance, communication barriers, and power dynamics in relationships. This also was of no surprise to me. Even when working with other prevention educators and victim advocates these are topics, they have rarely been exposed to much less trained on; this is the difference between someone who was training on the job and someone who is a scholar and researcher on a specific subject matter.

Few people will know exactly what tokenism is, much less how it is interconnected with consent. Tokenism is a direct component of communication barriers—understanding why victims have a hard saying no or setting clear boundaries is so crucial to understanding the affirmative dynamic of consent and yet is rarely discussed. Both tokenism and communication incongruences are wrapped in the mantle of power dynamics unless we can explain why different positions of power create different levels of comfort and afford varying levels of access to adequate and honest communication, we are still missing the mark on discussing consent holistically.